Collectie Soeterbeeck

- Radboud Universiteit

- Universiteitsbibliotheek

- Collectie Soeterbeeck

- English summary

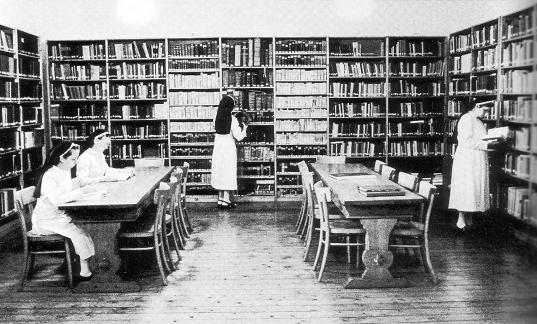

The old library of the convent of Our Lady (“Onze-Lieve-Vrouw”) of Soeterbeeck

At the end of the previous century the few remaining Augustinian nuns of the convent of Soeterbeeck in Deursen-Ravenstein, near Nijmegen, made the radical decision to continue their community and contemplative life in the home for elderly nuns in Nuland, and close down the convent. The buildings and their fittings, including the old library, were transferred to the Radboud University of Nijmegen in 1997, causing the university to come into possession of a collection of over 50, mostly liturgical, manuscripts, and several hundreds of printed books, dating from the late 15th to the 20th century.

It was not until 1732 that the convent of Our Lady (“Onze-Lieve-Vrouw”) of Soeterbeeck settled in Deursen-Ravenstein. Its roots are in Nederwetten, a small village near a brook called the “Suetbeeck,” within a stone’s throw from Eindhoven. The convent was started there in 1448 as a community of the Sisters of the Common Life. In 1452, these devout women requested permission of the bishop of Liège, John of Heinsberg, to adopt the Rule of St. Augustine, and permission was granted in 1454.

The nuns moved from the marshy soil of Nederwetten to the higher lying village of Nuenen near the river Dommel in 1462, and they were encloistered some years later. From then on the sisters lived only within the monastic enclosure.

From 1452 to 1744 the cura monialium, the pastoral care of the nuns, was entrusted to the Augustinian Canons of the monastery of Mariënwater in Woensel, also near Eindhoven. One group of liturgical manuscripts in the Soeterbeeck Collection was probably manufactured in this monastery.

In the fifteen-eighties the convent joined the Chapter of Venlo, which the bishop of Liège had established in 1455 for the benefit of the Augustinian nuns in his diocese. As a result of the closing or amalgamating of monasteries and convents in North Brabant due to regional troubles, the Reformation, and the Eighty Years’ War, books from at least three convents from this chapter eventually ended up in Soeterbeeck.

One of these convents, that of Onze-Lieve-Vrouw in de Hage (“Our Lady in the Hague”) in Helmond, first merged with the convent of Sint-Annenborch (“St. Anna’s Burrow”) in Rosmalen in 1543, after the former monastery had been destroyed to prevent occupancy by the troops of the notorious Guelderian field marshal Maarten van Rossem, who sacked the convent of Soeterbeeck later that same year. The nuns of the convent Sint-Annentroon (“St. Anna’s Throne”) in Kerkdriel joined those of the convent Sint-Annenborch in 1572. In the next year the community of Sint-Annenborch felt forced to take refuge in a monastery in Den Bosch, but in 1613 the community had to leave the monastery in favour of the Jesuits. Seven of the remaining nuns decided to continue their religious life in the convent of Soeterbeeck, near Nuenen, taking with them a large part of the monastic inventory.

In 1621 the convent of Soeterbeeck counted 17 choir sisters and eight lay or “converse” sisters, and in 1632 there were 26 sisters and one novice. The signing of the Peace of Münster in 1648 ushered in the last period of the “old” convent of Soeterbeeck, for in 1732 the nuns finally had to leave Nuenen. They settled on “Den Bongaert” (“The Orchard”), a rural estate near Deursen in the independent Land of Ravenstein.

There the community survived the French occupation of 1794. Though the end of the community seemed to be nigh on more than one occasion, the “new” convent of Soeterbeeck survived the nineteenth century. In 1954 the Windesheimer community of Mariëndaal, in Diest (Belgium), even amalgamated with the nunnery in Deursen. The curtain only fell in 1997, as the few remaining nuns moved to Nuland.

A first examination of the manuscripts has made clear that these books had been preserved because they had continued to be in use for centuries and – maybe more importantly – because of the frugality of their owners. Heavily used, repaired, and eventually unbound by the nuns themselves, a lot of them ended up defective, already partially used for binding purposes. The more substantial parts, torsos as it were, were ultimately only joined together, to judge by their simple cardboard covers, in order to preserve them.

Many of the printed books – most of them handy-sized – also show adaptations and extensions, among which substantial pieces of writing. Notes of ownership sometimes go hand in hand with small texts; there are traces of repair; books were rebound, partly with leaves of cut up manuscripts; and quite a few of them contain loose objects ranging from devotional pictures and mortuary cards to small pieces of textile.

Studying these books makes you aware of their multi-layered character and contexts in time. As such the Soeterbeeck collection delivers us an exceptional view at the individual and collective use and reuse of the manuscripts and printed books over a long span, leading to transformation and to loss as well to preservation.